In an earlier post, a bishop's stolen headgear got me thinking about the definition of art, the place of the artist in the body of Christ and the meaning of creativity.

So as I walked around the Kimbell Art Museum's excellent exhibit Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art, I wondered --is this really the earliest Christian art?

What about some guy who was whittling a stick into the shape of a dove while Peter was preaching a sermon? That would be art as an act of devotion. Where are those everyday equivalents to the mother goddess carvings that seem to be scattered around every neolithic village they excavate? Where are portraits or even remembrances of the face of Jesus? Or portraits of the apostles?

Not only are there no contemporary portraits of the leading figures of the early church, no one even attempted them, apparently, until a couple of centuries after the fact.

They either didn't exist or were ground to bits by the mill wheel of time. In fact, by "earliest," the exhibit means those pieces that were guarded and survived the persecutions, earthquakes, invasions and neglect of the centuries, either by chance, by design or by providence. If you acknowledge Christians could have been creating art soon after the crucifixion, there is a gap of about a century and a half before the earliest extant works. Even longer until this ceiling fresco, (above) c. 320 A.D. from the Coemeterium Maius (the large cemetery) near the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, or the ivory plaque (below) from the mid fifth century.

We know the first Christians were creative. Worship music was being composed right from the start-- a couple are set down for us in the New Testament. The Apostle Paul mentions "psalms and hymns and spiritual songs" as part of the earliest worship liturgy. These were mostly texts from the Old Testament, but brand new ones are recorded, too. There's no mention of painting, sculpture, mosaics or murals.

Several reasons for this are put forward in the exhibit's explanatory notes. I got a cramp scribbling them all down and then found out they have a book about the whole exhibit by guest curator Jeffrey Spier.

What the early Christian artists needed and didn't have was a rich patron. Art generally needs a sugar daddy to supply materials and support, Spier explains. Durable artworks couldn't be commissioned until Christianity was strong enough to include wealthier members who would pay for items that could be decorated with biblical images.

Next, there was a little thing called idolatry. The Jewish scriptures have a severe prohibition against idolatry, expanded by the Rabbis to include any artwork that might lead one's mind in that direction. This was strongest in Judea. It was only after Christianity had separated from its Jewish roots that those prohibitions were loosened or reinterpreted. At least that's the theory. Other experts insist that Jews were decorating their synagogues with murals and mosaics containing all manner of human and animal figures. But those examples were from outside of Judea, or after the first century, or both.

Another possible reason for the gap? The apocalyptic dimension of the kingdom Christians were proclaiming meant that this world-- including its artwork, architecture and social institutions--was slated for a drastic and fiery makeover.

Clement of Alexandria (150-215 A.D.) gives us the first documented mention of Christian art:

“And let our seals by either a dove, or a fish, or a ship running with a fair wind, or musical lyre, which Polycrates used, or a ship’s anchor, which Seleucus had engraved; and if the seal is a fisherman, it will recall the apostle, and the children drawn out of the water. For we are not to depict the faces of idols, we who are prohibited from attaching ourselves to them, nor a sword, nor a bow, since we follow peace, nor drinking cups, since we are temperate. Many of the licentious have their homosexual lovers engraved, or prostitutes, as if they wished to make it impossible ever to forget their erotic passions, by being continually reminded of their licentiousness.”

So, Christian porn was off limits! Clement apparently was not advocating creating new symbols, but explaining how to choose from among the many symbols already widely in use for Roman document seals, so that Christians could engage in business without endorsing pagan ideas. This passage is really about re-interpreting pagan symbols. A fish was a fish to a Roman. To a Christian it reflected the Greek acrostic ichthys, "Jesus Christ Son of God."

The earliest works in the Kimbell's exhibit are reproductions, because they couldn't ship the ancient sites to Fort Worth. They're 18th century watercolor copies of catacomb paintings decorating the secret underground places where Christians gathered to worship and bury their dead--for instance, the Catacombs of Domitilla and of Peter & Marcellinus in Rome, around 350 A.D. And they are mesmerizing.

The unnamed original artists don't rank with Michaelangelo. But considering the persecutions that led them to meet in hiding, these paintings--even secondhand-- exhibit a raw energy simply from the fact they were created at all.

The most eye-opening aspect of the exhibit is the subject matter: Jesus is depicted many times as a short-haired, beardless Good Shepherd with a lamb slung over his back. We expect the accompanying fish symbol and the dove, but an anchor? What's with that? Old Testament images dominate, but they're not always the stories we'd choose today. Jonah, for instance, is depicted all through the exhibit's works, not just being swallowed by the big fish, but relaxing under the gourd.

Why? Perhaps because the book of Jonah was one of the readings for the Jewish Feast of Yom Kippur, and Jesus himself made the connection between his death and resurrection and Jonah's three days in the belly of a whale.

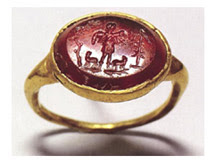

The Good Shepherd image, surprisingly, was not biblical. It was taken directly from a traditional and popular pagan image reproduced throughout the Empire. The ring from the late third century (shown above) is deciphered as Christian only because of the dove in the tree and the initials I H C X, an abbreviation for Jesus Christ.

As Spier explains it,

“Christian artists were able to appropriate this figure and invest it with purely Christian significance. Jesus explicitly stated: ‘I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep’ (John 10:11), and this passage was surely uppermost in the minds of Christians of the third and fourth centuries when they employed the image on their seal rings, gold glass cups, baptisteries, and tombs."Christians have been appropriating pagan cultural symbols, celebrations and architecture ever since, for good or ill. Some catacombs even have figures of Orpheus mixed in with biblical images. In fact, co-opting what's popular in secular society has today almost supplanted originality in every aspect of Christian media, but that's another story.

The earliest datable instance of the Good Shepherd motif may be the clay lamp (shown above) from the Florentius workshop made in the early third century. It also depicts Noah’s ark and assorted animals. A stamp on the underside identifies the workshop as Florentius, in or near Rome, which produced many lamps with pagan symbols, Spier says. Apparently much of Christian art, once it got rolling, may not have been produced by Christian hands at all. It might have been merely commissioned from a pagan artisan by a Christian, who requested the particular symbols and decorations. So, is it still Christian art? At some point, people stopped caring.

After all, if Kris Kristofferson can sing Jesus was a Capricorn, definitions are out the window.

The exhibit runs through the end of March.

Next time: What happened when Christianity became legal, then dominant, and finally produced the holy relic only Paul and Jan Crouch could love?

• Furl • StumbleUpon • Technorati Tags: Kimbell Earliest Christian Art, Christian humor, satire, humor

No comments:

Post a Comment